How to Invest in Stocks: The Ultimate Beginner's Guide

Folks like to complicate it, but investing is a simple game.

These pages contain a step-by-step, paint-by-numbers guide to making a fortune in stocks.

We believe anyone is capable of growing their wealth as an investor. You only need to know three things... and they work no matter what else is happening in the world or in the markets.

- First, the amount of capital employed is important. Thus, the cardinal rule is: Don't lose money. Money lost cannot be invested. Money lost will not compound.

- Second, time matters. How long you hold an investment for it to compound, year after year, is critical.

- And the third important factor is the rate of compound growth.

This comprehensive guide will walk you through the fundamentals of stock investing – from understanding what stocks are and why they're a powerful investment, to setting your financial goals, choosing the right brokerage, and making your first stock trade.

Along the way, we'll highlight key concepts and link to in-depth resources on specific topics so you can dive deeper as needed. This guide will give you a clear roadmap and practical tips as you start your investing journey.

Table of Contents

- How You Can Make $1 Million By Investing in the Stock Market

- What Is a Stock?

- Why Invest in Stocks?

- Where Does the Growth Come From?

- What You Need to Know About the Stock Market

- Before You Invest, Set Your Goals

- Simple Rules of Thumb for Saving and Investing

- Choosing a Brokerage and Understanding Account Types

- The Most Common Approaches to Investing

- Buy-and-Hold Investing

- Dividend Investing

- Value vs. Growth Investing

- Don't Put All Your Eggs in One Basket

- Always Protect Your Downside

- Stock Market Terms Every Beginner Needs to Know

- Welcome to Your Lifelong Investing Journey

How You Can Make $1 Million By Investing in the Stock Market

Practically anyone in America can be a millionaire.

You just need two things... Time and a good rate of return.

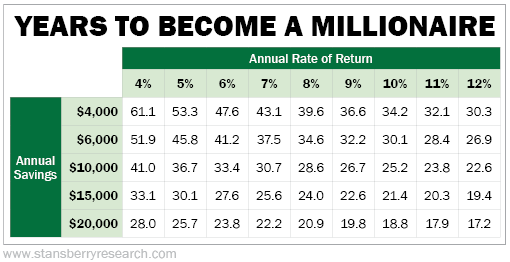

Take a look at the table below. It shows you how many years it will take you to become a millionaire based on how much you save each year and your annual rate of return.

For example, if you save $10,000 every year and earn 8% on your investment, you'd be a millionaire after 28.6 years...

Obviously, becoming a millionaire doesn't happen overnight. Anyone who tells you otherwise is either doing something illegal or highly risky. Avoid these "get rich quick" schemes like the plague.

Time is by far the biggest factor in planning for a successful retirement. The earlier you start saving and investing the better.

Thanks to the power of compounding returns, even if you start saving and investing just a few years earlier than your buddies, it can mean tens of thousands of extra dollars by the time you retire.

Every year of savings counts, even if you're not in your 20's or 30's. Don't put it off any longer.

The truth is that over time, investing in the stock market will make you money. Stocks are by far the best game in town.

If you're a serious investor, you need to own stocks. Plus, if you're an active investor and choose the right stocks, you can make more than the market every year.

So let's talk about the details...

What Is a Stock?

Stocks represent partial ownership in a business. When you buy a stock, also called a "share," you own a piece of the "equity" of the underlying business.

If the business does well, the value of your ownership can grow.

There are typically two main types of stock:

Common stock is what most people invest in – it usually comes with voting rights (so you can vote on things like electing the board of directors) and the potential for capital gains (if the stock's price increases) and sometimes dividends (if the company distributes part of its profits to shareholders).

Preferred stock, on the other hand, usually does not have voting rights but has a higher claim on assets and earnings. That means preferred shareholders get paid dividends before common shareholders, and have priority if the company were liquidated.

For most beginners, common stock is the focus, as it's the most straightforward way to participate in a company's growth.

And the potential upside in stocks is incredible...

Why Invest in Stocks?

Why put your money into stocks instead of safer assets like bonds or savings accounts? The short answer: That's where the growth is.

Historically, stocks have been the highest-returning mainstream asset class over the long term.

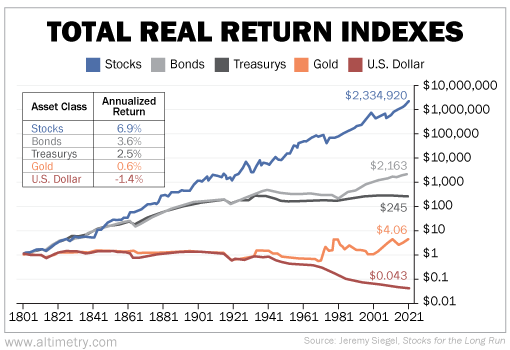

A recent Daily Wealth letter included a chart from the book Stocks for the Long Run by Wharton School of Business professor Jeremy Siegel.

Thanks to the compounding effect, $1 invested in stocks back in 1801 was worth $2,334,920 in 2021. The same amount invested in bonds over the same period only returned $2,163.

That astonishing difference comes from compounding – the process of earning returns on top of returns. When you reinvest your gains and hold for many years, those gains snowball...

In contrast, bonds and cash yield much less over time, often just keeping pace with or lagging inflation.

Where Does the Growth Come From?

Stocks also let you benefit in two ways:

Capital gains are the profits you earn when you sell a stock for more than you paid for it. If you buy shares at $20 and later sell at $30, that $10 difference is your capital gain (before taxes).

Dividends are portions of a company's profits that it may distribute to shareholders, typically on a quarterly basis. Not all companies pay dividends (many fast-growing companies prefer to reinvest profits back into the business), but many established firms do.

Dividends can provide you with a steady income stream and can be reinvested to buy more shares, which accelerates your compounding.

Over the long term, dividends have been a significant part of total stock market returns...

Renowned stock market analyst Dr. David Eifrig recently published a chart that shows the benchmark S&P 500 Index's return each decade since the 1930s. Over a span of 90 years, dividends were responsible for nearly 40% of the total market return. Take a look...

As Doc Eifrig emphasizes, "Dividends compound your capital. Every quarter, you have more money to invest than before. This lets your gains multiply over the long term."

Another big reason to invest in stocks is that they typically outpace inflation. Inflation is the rise in cost of living over time – it erodes the purchasing power of money.

Leaving all your savings in cash means inflation will slowly chip away at its value. Stocks, by virtue of representing real businesses that have pricing power and assets, tend to rise in value along with (and well above) inflation over long periods.

In other words, stocks give you a claim on productive enterprises, which is a great hedge against inflation and the U.S. dollar losing value.

Bottom line: If you want your money to grow meaningfully, stocks are hard to ignore. They come with short-term volatility (which we'll discuss), but for long-term investors who can ride out the bumps, stocks have historically rewarded that patience with unmatched gains.

What You Need to Know About the Stock Market

You'll buy most stocks via the stock market. That just means a marketplace of buyers and sellers. Typically, most stocks that you'll hear about trade on major exchanges like the New York Stock Exchange ("NYSE") or Nasdaq.

Stock prices fluctuate constantly during market hours as investors buy and sell. These price movements are driven by supply and demand in the market – influenced by factors like the company's performance, economic conditions, and investor sentiment. But at its core...

- If there is more demand, meaning more people want to buy a stock than sell it, the price rises.

- If there is more supply, meaning more want to sell than buy, the price falls.

This continuous auction is what sets the price of each stock at any given moment.

You'll often hear about market benchmarks like the S&P 500, the Dow Jones Industrial Average, or the Nasdaq Composite. These indexes track the performance of a broad basket of stocks (500 large U.S. companies in the case of the S&P 500, 30 blue-chip companies for the Dow, etc.).

They serve as a barometer for "how the market is doing."

Historically, the S&P 500 is often considered the market proxy. It returns around 10% annually on average, though any given year can be +30% or -20% or anything in between.

When you invest in stocks, one benchmark of success is whether you can match or beat index returns over the long run. Many investors choose to simply invest in index funds (more on this later) to capture that market return without trying to pick individual stocks.

It's important to remember that as a shareholder, you're in it for a piece of the business. If the business does well over time, the value of your share tends to rise. If the business struggles, your share value can fall.

In short, a stock's price reflects what investors think the company is worth at a given moment, which can sometimes diverge from the company's actual long-term value.

Consider if you bought all the stocks in the market, 20 years ago. Over that time, some businesses have failed, and others have grown.

That's because short-term market moves are unpredictable. Stock prices can swing day-to-day or month-to-month for reasons that are often unexpected: an earnings report, economic data, Federal Reserve interest rate changes, geopolitical events, or even just investor moods.

As a beginner, you should be mentally prepared for the fact that even "good" stocks do not go up in a straight line. It's not unusual to see stock indexes (like the S&P 500) drop 10% (a correction) or even 20%+ (a bear market) temporarily. The key is to not panic during these swings.

If you had held those businesses over the past 20 years... you would have seen multiple recessions, wars, global pandemics, and all kinds of market chaos. During those rough patches, your holdings of businesses would have appeared to be worth much less. But over time, your investments grew and gained value.

Overall, if you owned "all the business" of the economy, you'd have earned a great return...

Before You Invest, Set Your Goals

One of the first steps in crafting your investment plan is to define your financial goals and the timeline for each goal.

Are you investing for a retirement that's 30 years away? Saving for a down payment on a house in 5 years? Building an emergency fund?

The answers will determine how you should invest in stocks (or whether you should invest in stocks at all for a given pot of money).

A fundamental rule: Only invest in stocks with money you won't need in the near future. Stocks are best for long-term goals.

Because of their short-term volatility, you don't want to be forced to sell stocks to raise cash for an immediate need (like buying a car or covering an emergency expense) right after the market drops. If your timeline is too short, you might not recover in time.

Many investors recommend a "bucket" strategy for your money based on when you'll need it:

- Immediate needs (0–2 years): Keep this money in cash or cash equivalents. This is your safety bucket – an emergency fund or any savings for imminent expenses. In other words, don't gamble money you need next year on the stock market. Keep it in a high-yield savings account, money market fund, or short-term CD where it's safe (and liquid).

- Short-term goals (2–5 years): Consider more stable, income-oriented investments like bonds for this bucket. Bonds (or bond funds) typically fluctuate much less than stocks and can provide modest growth with lower risk. The idea is capital preservation takes priority over high growth when your time frame is only a few years.

- Medium-term goals (5–10 years): This bucket can be a balanced mix of stocks and bonds. If your goal is, say, 7 or 8 years away, you have some time to ride out market swings, but not a full decade. One approach is to adjust the stock vs. bond mix based on market conditions and your risk tolerance. In practice, this could mean maybe a 50/50 or 60/40 stock-to-bond ratio (leaning more toward stocks if things look positive). The goal is to get some growth from stocks but have bonds as a cushion in case stocks hit a rough patch.

- Long-term goals (10+ years): This is your stock-heavy or all-stock bucket – money you won't touch for a decade or more can be fully invested in equities for maximum growth. Over such long periods, stocks historically have no competition in terms of returns. By staying invested at least 10 years, you greatly increase the likelihood of riding out any bear markets and coming out ahead. As mentioned earlier, the odds of losing money in stocks drops the longer you hold – a decade or more has almost always been rewarded with a positive return in the past.

By setting clear financial goals and matching your investments to your timelines, you'll take on an appropriate level of risk.

This planning also helps manage your expectations – for example, you won't be upset that your "house down payment fund" in bonds isn't growing as fast as stocks, because you intentionally chose safety there. Conversely, you won't touch your retirement stock investments for quick cash because you've segregated money for near-term needs elsewhere.

A few more goal-setting tips:

- Define each goal specifically and put a dollar amount on it. "Retirement in 30 years with $X per year in income," or "$50,000 for a home down payment in 5 years," etc. This gives you a target to plan for (and you can use online calculators to estimate how much to invest monthly to reach it, given assumed rates of return).

- Prioritize and sequence your goals. If you're younger, retirement might be your biggest investing goal, but don't forget to build an emergency fund first (3–6 months of expenses in cash) and pay down high-interest debt. Those steps come before heavy stock investing. If you have multiple goals (college savings, a new house, etc.), decide which is most important and fund each bucket accordingly.

- Revisit and adjust over time. Goals and timelines can change. Maybe your 10+ year goal becomes a 5-year goal later (or vice versa). Gradually shift the asset allocation of a bucket as the target date approaches – for instance, as a goal moves from 10 years out to 5 years out, you might start dialing back the stock portion and adding more bonds or cash to lock in gains and reduce risk.

The takeaway is: invest with purpose. Don't just throw money into stocks blindly. Tie each investment to a goal and a time horizon. This will guide your choice of investments and make it easier to stick with your plan through market fluctuations.

Simple Rules of Thumb for Saving and Investing

Let's say you're a 40-year-old who makes $100,000 a year. And up to this point, you haven't taken retirement seriously. You haven't setup a 401(k) yet. You spend too much on travel and food. And you aren't interested in the stock market.

The good thing though is that time is still on your side – even though you're late to the game. All it will take is a small amount of discipline and a simple S&P 500 fund.

If you save 20% of your salary every year – this includes any money you put into your 401(k) plus any employer match – and put that money into a S&P 500 fund, you can be a millionaire by the time you're 59 (assuming a 10% annual rate of return.) If you plan to retire by 67, and bump your savings rate up a little bit in the last eight years of your working life, you can get close to the $1.9 million mark to retire comfortably.

But then again, not everyone will need $1.9 million for their retirement.

A common rule that you've likely heard before is the "70%/80% rule." This means that you should aim to replace about 70% to 80% of your salary in retirement.

So if you made $100,000 annually before you retired, you should ideally have $70,000 to $80,000 a year to maintain your standard of living. This can include portfolio withdrawals, Social Security, pensions, and other sources of income.

The only problem is that many retirees find themselves spending more than 70% to 80% of their pre-retirement income – especially in the first few years after leaving the workforce.

Your costs get eaten up by having more time... You may find yourself traveling more, going out to eat more, and spending more on new hobbies. Plus, the cost of health care adds up quickly as you get older.

There's also something called the "4% rule." Take your desired annual income in retirement and divide it by 0.04. This will give you an estimate of how much you need saved for retirement.

So if you imagine that you will need $60,000 a year in retirement, you'd need a nest egg of $1.5 million ($60,000 divided by 0.04).

Another way to make sure you're on track for your retirement is by following a general outline based on your annual salary and age. The benchmarks below, provided by Fidelity, can help make sure you are saving enough throughout your life...

- At age 30, you should have one times your annual salary saved

- At age 35, two times your annual salary

- At age 40, three times your annual salary

- At age 45, four times your annual salary

- At age 50, six times your annual salary

- At age 55, seven times your annual salary

- At age 60, eight times your annual salary

- At age 67, 10 times your annual salary

Finally, a simple way to think about how much you should save is with the "50/30/20 rule." This is a broad guideline where 50% of your income (at maximum) should go toward your bills and necessities, 30% is your play money, and 20% should go toward savings.

These are all general guidelines to help you think about saving for retirement. But there's really no one answer for what amount of money you need to retire comfortably...

Perhaps the best method, especially if you're getting close to your retirement age, is to write down all of your projected expenses while retired. Think of all your bills and also include things like how many vacations you plan to take per year. You can then work your way back to calculate how big of a nest egg you'll actually need and what your actual replacement rate will be.

Also consider that life will undoubtedly get more expensive in the future, not less... So try to save a little more than you think you'll need.

If you're struggling to know how much of your income to save each year, I like to tell folks to save at minimum 12% to 15% of their salary... and to invest that money.

As always, the earlier the better.

If you've been putting off thinking about your retirement and how you'll fund it, it's time to start now.

Choosing a Brokerage and Understanding Account Types

To buy stocks, you'll need a brokerage account – this is an account with a financial institution that allows you to trade stocks (and other securities like ETFs, options, etc.). Choosing a brokerage is an important practical step for a beginner. The good news is that today it's easier and cheaper than ever to open a brokerage account online.

What to look for in a brokerage:

- Low fees: Most major brokers now offer commission-free stock trades, which is great for investors. Make sure the broker doesn't charge hidden fees for things you plan to do. Look at fees for account maintenance, transfer, or if you plan to invest in mutual funds, see if there are fees for those. Fortunately, many brokerages have minimal fees beyond tiny spreads.

- User-friendly platform and tools: If you're a beginner, you want a broker with an easy-to-navigate website or app, good customer service, and educational resources. Some brokers cater to buy-and-hold investors, while others have more sophisticated trading tools – pick what suits your style. You might check out a few demos or reviews. Stansberry's experts often favor well-established firms – any of the top reputable firms should get the job done for a retail investor.)

- Product availability: Ensure the brokerage offers the investments you want. Almost all will offer U.S. stocks and ETFs. If you also want to buy bonds, mutual funds, or international stocks, verify those are available. Also, see if they offer IRAs (individual retirement accounts) if you plan to invest in a tax-advantaged way (more on IRAs shortly)

- Convenience and other benefits: Consider things like: Is there a minimum balance requirement? Do they offer banking services, check writing, or a good cash sweep interest rate? Do they have a local branch (if you desire in-person service)? These might be secondary factors but can tip the scales if you're deciding between comparable brokers.

Opening an account is usually straightforward: you fill out an online application, provide proof of identity (Social Security number, driver's license, etc.), and fund the account via bank transfer. Within a couple of days, you're ready to invest.

When opening a brokerage account, you'll typically be asked what type of account you want. The main choices are a standard (taxable) account or a type of retirement account (tax-advantaged). It's crucial to understand the difference:

- Standard Brokerage Account (Taxable): This is the default. You deposit money, invest in whatever you like, and you'll pay taxes each year on any dividends or interest, and on any capital gains when you sell investments. There are no special tax breaks, but also no restrictions on when you can withdraw money (aside from potential trading fees or taxes on gains). Use this for general investing or goals prior to retirement age.

- Individual Retirement Account (IRA): An IRA is a special type of brokerage account designed for retirement savings, offering tax advantages to encourage you to invest for the long term. Think of it like a regular brokerage account, but with an IRS twist – it's "sheltered" for retirement. There are two main types:

-

- Traditional IRA: In a traditional IRA, you often get a tax deduction on contributions (if you meet certain conditions) – effectively, you're investing pre-tax dollars. The money grows tax-deferred, meaning you don't pay taxes on dividends, interest, or capital gains each year while the money stays in the account. Instead, you pay ordinary income tax on withdrawals in retirement. Basically, it's "tax later." This is great if you expect to be in a lower tax bracket when you retire, or you just want a tax break now. There are annual contribution limits (for example, $6,500 per year if you're under 50, as of 2023) and you generally cannot withdraw before age 59½ without a penalty (with some exceptions).

-

- Roth IRA: A Roth IRA is sort of the mirror image: you contribute after-tax money (no upfront deduction), but then it grows tax-free and qualified withdrawals in retirement are tax-free as well. It's "tax now, invest, then no tax later." If you expect to be in a higher tax bracket in the future, a Roth is appealing – pay tax on contributions now at a lower rate, and avoid tax on potentially much larger withdrawals later. Roth IRAs also have income eligibility limits (if you earn too much, you can't contribute directly). Both traditional and Roth IRAs have the same contribution limits, and both allow you to invest in a wide range of stocks, bonds, funds, etc. within the account.

In summary: In a traditional IRA, your contributions may be deductible and growth is tax-deferred (taxed on withdrawal). In a Roth IRA, contributions are not deductible, but growth and withdrawals are tax-free. As one Health & Wealth Bulletin article put it, a Roth is a "flipped version" of a traditional IRA – no tax break going in, but no taxes coming out.

- 401(k) and other employer plans: While not a brokerage account you open on your own (it's provided via your employer), it's worth mentioning: if your employer offers a 401(k) or similar retirement plan, definitely take advantage of it, especially if there's an employer matching contribution (that's free money!). Contribute at least enough to get the full match. You can always invest in individual stocks within a self-directed 401(k) or after rolling a 401(k) into an IRA later. Many people invest in broad mutual funds through their 401(k) and then use a separate brokerage account for additional stock investing.

Which should you choose? If you're investing specifically for retirement, an IRA is usually a smart move because of the tax benefits. If you're investing for a nearer-term goal or you've maxed out your IRA contributions, then a taxable brokerage account is fine.

In many cases, investors have both – for example, you might max out an IRA each year for retirement savings, and also invest extra savings in a regular brokerage account for flexibility. Remember, money in an IRA is somewhat locked up until retirement age (barring certain exceptions or paying a penalty), so don't put all your savings into an IRA if you'll need some before age 59 ½.

The good news is opening an IRA is as easy as opening a normal account – with most brokers, it's just a matter of selecting "Traditional IRA" or "Roth IRA" on the account application. It might take a few extra steps (like indicating beneficiaries), but it's straightforward.

One strategy some experts recommend if unsure about future taxes is to diversify your account types – contribute to both a traditional and a Roth if you're eligible, so you have a mix of tax-deferred and tax-free money in retirement This way, you can pull from either pot depending on what's optimal tax-wise down the road.

Action to take: Pick a solid brokerage, and use the right account type for your needs. Read more by clicking here for our full guide on opening a brokerage.

For most beginners, a good approach is to open a Roth IRA (for retirement investing if you qualify) and/or a regular brokerage account (for other investing) at a reputable firm. This gives you the platform to start buying stocks and building your portfolio in a tax-efficient way.

The Most Common Approaches to Investing

There are many ways to invest in stocks, and part of your journey is deciding which investment approach suits your goals, personality, and resources.

Here we'll cover a few fundamental strategies/styles... but please keep in mind, these approaches aren't mutually exclusive – you can blend elements of each depending on your own financial goals...

Buy-and-Hold Investing

Buy-and-hold is a straightforward long-term strategy: you buy stocks (ideally shares of great businesses or broad index funds) and hold onto them for a long period, regardless of short-term market fluctuations. The idea is to benefit from the power of compounding and the fact that quality companies tend to appreciate in value over years and decades. This strategy contrasts with active trading, where someone might frequently buy and sell to time the market. (Learn more about active trading and technical analysis here.)

Advantages of buy-and-hold:

- It's simple and time-efficient. You don't have to constantly monitor the market or make frequent decisions. Legendary investors like Warren Buffett advocate this approach, often saying their favorite holding period is "forever" for the right stocks.

- It minimizes costs and taxes. Frequent trading can rack up commissions (though less of an issue now with $0 commissions) and trigger short-term capital gains taxes. Holding for over a year qualifies you for lower long-term capital gains tax rates, and holding indefinitely defers taxes completely until you sell.

- It plays to the long-term upward bias of markets. By staying invested, you ensure you don't miss the big up moves that are hard to predict. Studies have shown that missing just a handful of the market's best days can dramatically reduce your overall returns. Buy-and-hold ensures you capture those gains.

The key, of course, is what you buy and hold. Ideally, you want to invest in high-quality, durable companies or low-cost index funds.

Stansberry's analysts often talk about focusing on "World Dominator" companies – businesses with strong competitive advantages, consistent earnings, and a history of rewarding shareholders.

If you fill your portfolio with solid companies bought at reasonable prices, a buy-and-hold approach can be very rewarding. Over such long stretches, the day-to-day noise fades away and what matters is the company's cumulative growth.

Buy-and-hold does not mean "set it and forget it completely" or "hold losers forever." It's important to monitor your holdings and the business fundamentals. If the reason you bought a stock no longer holds (say the company's competitive advantage disappears or it starts performing very poorly), then selling is justified. The goal is to hold long term, but only as long as the investment thesis remains intact.

Overall, buy-and-hold is a great default strategy, especially if you're investing in broad index funds or a basket of strong companies. It's essentially "patience as a strategy." By not over-trading, you let the businesses do the work and allow compounding to work its magic.

Learn more about the advantages of fundamental and technical analysis right here.

Dividend Investing

Dividend investing is a strategy that focuses on stocks that pay dividends – regular cash payouts to shareholders. The goal may be to generate a steady income stream, to reinvest those dividends for faster growth, or ideally both. This approach often appeals to investors seeking passive income (like retirees) or those who appreciate the relative stability of dividend-paying companies.

Key points about dividend investing:

- Dividend stocks tend to be mature, stable companies. Companies that pay dividends are often well-established, with reliable profits – think companies like Coca-Cola, Johnson & Johnson, or utility companies. They tend to be past the high-growth startup phase and are now sharing profits with owners. These stocks may not skyrocket like a hot tech startup, but they often hold up better in weak markets and deliver more consistent returns through their dividends.

- Reinvesting dividends accelerates growth. By enrolling in a DRIP (Dividend Reinvestment Plan) or simply using your dividends to buy more shares, you can compound your returns. Every dividend you reinvest buys you more shares, which then themselves produce more dividends. Over time this "snowball" can become significant. Dividends help compound your capital – each payout gives you more to invest, which lets your gains multiply.

- Dividend yield and growth are both important. A stock's dividend yield is its annual dividend per share divided by its share price – it's the effective interest rate of the stock in terms of cash payout. For example, if a stock pays $1 per year in dividends and is priced at $20, its yield is 5%. While a high yield can be attractive, it's not the only thing to look at. Sometimes an extremely high yield is a red flag (it could imply the stock price fell a lot or the dividend might be unsustainable). Equally important is the dividend growth rate – does the company consistently increase its dividend over time? Companies that steadily grow their dividends (like the "Dividend Aristocrats" that have 25+ years of dividend increases) have historically been excellent investments. The lesson: quality and growth of dividends often beat just chasing yield. Owning stocks that can raise their dividend year after year is a "smart move," as those companies have strong and improving fundamentals.

- Safety of the dividend matters. Look at metrics like the payout ratio (what percentage of earnings are paid as dividends). If a company is paying out, say, 80% or more of its profits as dividends, there's little room for error or for raising the dividend further – any downturn could force a cut. Many dividend investors prefer companies with moderate payout ratios (perhaps 60% or less) and manageable debt, which imply the dividend is on solid ground. It's better to have a slightly lower yield that's rock-steady (and growing) than a sky-high yield that could be slashed (which often also hurts the stock price).

A dividend strategy could be executed by picking individual dividend stocks or by buying mutual funds/ETFs that focus on dividend payers. If selecting individual stocks, you might look for a combination of decent current yield (for income now) and a track record of dividend increases (for income growth later). Sectors traditionally rich in dividend payers include consumer staples, utilities, telecoms, healthcare, energy, and financials.

Keep in mind, dividend investing is not mutually exclusive from buy-and-hold – in fact, it pairs perfectly with it. The longer you hold a good dividend stock, the more cumulative cash you'll receive. There's a concept called "yield on cost" – if you buy a stock at $20 with a $1 dividend (5% yield), and the company raises that dividend to $2 over years while you still hold, your yield on the original cost is now 10%. Long-term dividend investors often find that their yield on cost becomes extremely high on stocks they've held for a decade or more, essentially generating large cash returns relative to their initial investment.

To sum up, dividend investing can provide a reliable return component in your portfolio. Many of the stock market's historical returns have come from dividends, so it makes sense to pay attention to them. Just ensure you focus on sustainable dividends from healthy companies. A portfolio of strong dividend growers can be both an income generator and a wealth builder.

Value vs. Growth Investing

"Value" and "Growth" are two fundamental styles of stock investing, often thought of as opposites on a spectrum. Understanding the distinction will help you recognize different opportunities and strategies:

- Value Investing: This approach involves looking for stocks that are undervalued or "cheap" relative to their intrinsic worth. Value investors typically focus on metrics like the price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio, price-to-book ratio, or other fundamentals, trying to find companies that are out of favor or overlooked by the market. The classic scenario is a solid company with temporarily bad news or in a dull industry – its stock price is beaten down, but the core business is sound and the assets or earnings justify a higher price. Value investors aim to buy at a discount (a margin of safety) and then hold until the market recognizes the real value, at which point the stock price rises. The ethos is essentially "buy $1 worth of assets/earnings for 50 cents."

- Growth Investing: This approach seeks companies that are growing quickly – in revenues, earnings, or market share – even if their current stock price is not cheap by traditional metrics. Growth investors are willing to pay a premium for companies that are expanding rapidly, often in emerging industries or with innovative products. These stocks tend to have higher P/E ratios (market is pricing in high future growth). The bet is that the company's earnings will increase so dramatically in the future that today's expensive-looking price will end up justified (or seem cheap in hindsight). Think of companies like cutting-edge tech firms which may not have huge profits now but are scaling up users and could dominate their markets in a few years.

In practice, the line can blur – many successful investors blend both considerations, and a company can be both a growth and a value play at the same time if you believe its growth prospects are not fully appreciated (often called "GARP" – Growth At a Reasonable Price). But it's useful to understand the philosophical difference: value is about price relative to current fundamentals, growth is about potential future fundamentals. Learn more about fundamental analysis here.

Which performs better? This is a decades-old debate. Over very long periods, value investing has shown an edge.

For instance, Bank of America Merrill Lynch studied almost 90 years of data (1926–2015) and found that value stocks returned ~17% annually, compared to ~12.6% for growth stocks. Value, in the long run, trounced growth – higher returns with arguably lower risk (because you're buying cheap). This supports the famous quote by investing legend Joel Greenblatt: "All investing is value investing. The rest is speculation."

The idea is that ultimately, if you're not considering the value you're getting for the price you pay, you're just speculating. Even a growth investor wants the company to eventually justify the price with real earnings – otherwise it wasn't truly an investment, just a gamble on market sentiment.

However, there are periods when growth dramatically outperforms value (late 1990s, or the late 2010s tech boom, for example), and vice versa. Markets are cyclical. A growth stock can deliver spectacular returns if you pick a big winner (think early investors in Amazon or Apple). But growth stocks can also be riskier – if the anticipated growth doesn't materialize, their high valuations can collapse fast. As Dan Ferris wrote, "At best, growth investing is a speculation that a company will someday grow into a valuation that's overpriced based on today's performance."

In contrast, value stocks are often more boring businesses or turnarounds that might not shoot out the lights, but if bought cheap enough, they have a margin of safety (their fundamentals or assets protect the downside). Value investing tries to "keep your principal safe" by not overpaying.

A balanced view: Both value and growth can work, and both can fail.

The most famous investors span the spectrum – Buffett started more as a deep value investor and shifted to buying quality growth companies at fair prices (a blend). Peter Lynch famously invested in growth stocks but paid attention to P/E relative to growth (the PEG ratio).

What's important is your approach and temperament...

Value investing requires patience to wait for the market to recognize value; sometimes you can be "right but early" and it's frustrating.

Growth investing requires conviction in a company's future and tolerance for possibly high volatility (growth stocks can swing wildly on news and sentiment).

Some investors like to have both: a core of value plays and some growth stocks for upside.

Also, consider diversifying across styles. Often when growth stocks are in favor, value lag, and vice versa. For example, after the dot-com bust in 2000, value stocks massively outperformed for several years while many growth tech stocks languished. Then in the late 2010s, big tech growth names led the market and many value sectors (like energy or financials) lagged until a reversal around 2021. These cycles can shift unpredictably.

Stansberry Research's philosophy tends to lean value-oriented (seeking good businesses at good prices), but they also recognize great growth stories. Try using the Stansberry Score to evaluate an investment before you make it... learn more by clicking here.

Action to take: If you're a beginner, you might start with a slight value tilt (to avoid overpaying) but also include broad market index funds (which naturally include both value and growth). As you get more experienced, you can venture into identifying specific value plays (like a stock that looks cheap compared to its assets or earnings) or specific growth plays (a company with a disruptive technology).

Just always be mindful of the price vs. prospects trade-off. A great company can be a bad investment if you pay too high a price, and a struggling company can be a great investment if you get it for peanuts and it turns around.

The sweet spot is finding a great company at a good price – that's the holy grail that legendary investors seek...

Don't Put All Your Eggs in One Basket

No matter which stocks you pick or which strategy you follow, one concept will always be your safety net:

Diversification simply means spreading your investments across different assets, industries, or categories so that you're not overly exposed to any single one. It protects you from the unknown and ensure that a bad stroke of luck doesn't wipe you out.

In stock investing, diversification can take several forms:

- Owning multiple stocks instead of just one or two. This is basic: if you put all your money in one stock and that company hits hard times, your portfolio is devastated. If you own 20 stocks and one blows up, it's only a 5% hit (assuming equal weighting). A common rule of thumb is to hold at least 15-20 stocks across a variety of sectors to achieve decent diversification of company-specific risk.

- Diversifying across sectors and industries. You don't want all your stocks to be, say, tech companies or all bank stocks. Different sectors perform differently under various economic conditions. For example, during a recession, consumer staples (like food and household products) might hold up well while cyclical industries (like luxury goods or travel) suffer. If you were 100% in travel stocks, you'd be hurting. But if you had some staples, some healthcare, some tech, some finance, etc., a downturn in one area might be offset by stability or gains in another. Try to own businesses in different fields – e.g., some technology, some consumer goods, some industrial, some financial, some healthcare, etc.

- Including other asset classes. While this guide focuses on stocks, remember that a fully diversified portfolio often includes other assets like bonds, real estate, commodities, or cash. Stocks should be the growth engine, but holding some bonds or gold or real estate can reduce overall volatility. For instance, bonds often go up or hold steady when stocks go down (especially government bonds), providing a buffer. Asset allocation (the mix of stocks, bonds, etc.) is a form of diversification at a higher level.

- International diversification. Investing in companies from different regions or countries can add another layer of safety. U.S. markets don't always outperform – there have been decades where international stocks did better. If you only invest in your home country, you're making a bet (perhaps an okay bet, but a bet nonetheless) that it will continue to do well economically. Adding some international stocks or funds can hedge that. Many big U.S. companies are global anyway, but it can still help to own, for example, some emerging markets exposure because those economies might grow faster (albeit with higher risk).

One easy way for beginners to diversify broadly is through index funds or ETFs. If you buy an S&P 500 index fund, you instantly own a slice of 500 companies across all major industries – that's diversified equity exposure in one product. ETFs are particularly handy. They allow shareholders to get liquid, "one-click diversification" over a large cluster of assets. They are essentially exchange-traded mutual funds.

For example, a total stock market ETF gives you exposure to thousands of companies. There are also ETFs for sectors, for international markets, etc. Similarly, an index fund (which can be an ETF or a mutual fund) passively tracks a market index, giving broad exposure and often at very low cost. Index funds are a form of passive investing that regularly outperforms most active stock pickers over the long run, precisely because they are diversified and low-cost.

The main pitfall to avoid is concentration risk – having too much in one investment. That includes not just individual stocks but any correlated investments. For example, if you own five different oil companies, you may think you have five stocks (which you do), but you're not diversified because if oil prices crash, all five will likely drop together. Same with owning multiple companies that are all dependent on the same factor (interest rates, consumer spending, a big customer, etc.). True diversification means your investments don't all move in the same direction for the same reason.

Diversification is often called "the only free lunch in investing" because by mixing assets you can potentially reduce risk without sacrificing return. So, ensure your portfolio has variety. It's fine to have focused convictions (say you really believe in tech, so you overweight tech stocks), but even then, hold a mix of names and some non-tech exposure.

Always Protect Your Downside

The other big safety net you can use is via risk management.

Investing always involves risk – you can't eliminate it, but you can manage it smartly. Risk management is about mitigating losses when things don't go as planned. Here are some essential risk management tools and principles:

- Position Sizing: This means deciding how much of your portfolio to put into any single investment. Even if you have a high conviction stock idea, it's prudent not to make it too large a percentage of your holdings. For instance, you might limit any single stock to 5% or 10% of your total portfolio. That way, if one blows up, it won't ruin you. Position sizing goes hand in hand with diversification – it's the quantitative side of making sure you're not too concentrated.

- Stop Losses / Trailing Stops: These are sell orders set to trigger if a stock price falls to a certain point. A stop-loss order might say "sell this stock if it drops 20% from my purchase price" – it's a way to cap your potential loss on that position. A trailing stop is a dynamic version that moves up as the stock price rises, usually set as a percentage. For example, you could use a 25% trailing stop: if the stock climbs to $100, the stop would be at $75 (25% below $100). If the stock keeps going to $120, the stop moves to $90 (25% below $120). If the stock then starts falling and hits $90, it triggers a sell, locking in your gain from $50 or wherever you bought up to that $90 exit. Trailing stops thus protect profits and limit losses. Brett Eversole says, "A simple 25% trailing stop works wonders to limit your overall risk. A trailing stop rises as your position rises. Then, if your investment ever falls more than 25% below its most recent high, you sell. It's that easy. Stop losses limit your overall risk, plus they give you a concrete plan for when to sell." The peace of mind from having an exit strategy can be huge. It also removes emotional decision-making – you don't have to agonize in the heat of a downturn; the decision is made in advance.

- Avoiding Margin (for beginners): Margin means borrowing money from your broker to buy more stock than you could with your cash alone. While margin can amplify gains if you're right, it also amplifies losses and can even get you wiped out (via a margin call) if your stocks fall too much. It's generally recommended that beginners do not use margin. Invest with the cash you have. Only sophisticated investors who thoroughly understand the risks should consider margin, and even then, very cautiously.

- Hedging (advanced): Some investors use techniques like options or inverse ETFs to hedge (protect) against downturns. For instance, buying put options can limit your downside on a stock or index. These are more advanced tools and usually not necessary for a long-term investor who is properly diversified and not overextended. They can be useful in certain scenarios, but they often come at a cost (option premiums, etc.). If you're new, it's fine to skip hedging strategies until you're more experienced.

- Rebalancing: Over time, some of your investments will grow faster than others, and your allocation can drift. For risk management, it's wise to periodically rebalance – i.e., sell a bit of what's gone up (selling high) and/or add to what's gone down or lagged (buying low) – to maintain your intended risk level. For example, if stocks have a huge rally and were 60% of your portfolio but are now 75%, you might rebalance by trimming some stocks and adding to bonds or cash to get back to 60%. This ensures you don't inadvertently become too stock-heavy right before a possible downturn.

- Psychological Discipline: Perhaps the most underappreciated aspect of risk management is managing your own behavior. We are often our own worst enemies in investing. Fear and greed can lead to irrational decisions – panic selling at bottoms, or overbetting at tops. Setting rules (like the stop losses, position limits, etc., mentioned above) helps remove emotion. Also, having a long-term mindset helps – if you've done your homework and have confidence in your investments, you're less likely to panic sell on every dip. Remember that volatility is not the same as risk if you don't sell; it's only a permanent loss if you sell at a low. So part of risk management is ensuring you can stay in the game: don't invest money you can't afford to tie up, so that you're not forced to sell at a bad time. Keep some cash reserves for emergencies so your investment plan isn't derailed by an unexpected expense.

Stansberry analysts often remind readers that the biggest risk is not sticking to a plan. You can have the best strategy in the world, but if you abandon it in a moment of fear, it won't benefit you. "The real risk is that you'll screw [things] up because you're an emotional human being," as Dan Ferris put it, and end up selling at the wrong time or deviating from your strategy. Thus, set risk management rules when you're calm, and follow them when things get turbulent.

In practice, say you decide: I will hold ~20 stocks, no stock will be more than 10% of my portfolio, I will use 25% trailing stops on each position, and I will rebalance annually.

That's a simple risk framework. It doesn't guarantee success, but it does guarantee that you won't lose more than 25% on any single position (unless there's an overnight gap or something beyond control), and you won't have one bad pick destroy your wealth, and you'll systematically take profits and control losses. That already puts you way ahead of many investors who operate with no safety nets.

To conclude, diversification and risk management might not be the most exciting parts of investing, but they are absolutely crucial for longevity and ultimate success.

Think of it like defense in sports – you need a good defense to win championships, not just offense. By spreading out your bets and protecting the downside, you ensure that you can stay in the market long enough to reap the rewards.

Stock Market Terms Every Beginner Needs to Know

As you embark on your investing journey, you'll encounter a lot of jargon.

Don't be intimidated – once you get the hang of a few key terms, you'll be "speaking the language" of the market. Below is a handy glossary of stock market terms every beginner should understand:

Stock (Equity): A share of ownership in a company. Owning a stock makes you a shareholder – a partial owner entitled to a portion of the company's profits and assets. Companies issue stock to raise capital for growth. Stocks are also called equities. When you buy one, remember you're buying a piece of a business (as discussed, "a stake in a company").

Bull Market vs. Bear Market: A bull market is a prolonged period of rising stock prices (generally, when indexes rise 20% or more from a prior low and continue upward). It's a time of investor optimism and easy gains – the "bull" is charging ahead. A bear market is the opposite – a prolonged decline in prices (20% or more down from a peak), accompanied by pessimism. In a bear market, stock values are "mauling" portfolios like a bear's attack. Historically, bulls last much longer than bears, but bears can be sharp and painful. It's important to know which environment you're in, but also note that trying to predict or time bull vs. bear phases is very difficult (hence our emphasis on long-term investing).

Diversification: The practice of spreading your investments across different assets and securities to reduce risk. In plain terms, "don't put all your eggs in one basket." Diversification ensures that if one investment performs poorly, it won't sink your entire portfolio. For example, owning 10-20 stocks in various sectors (or a broad index fund) is far safer than betting everything on one stock. ETFs (see below) are a convenient way to achieve instant diversification.

Portfolio: The collection of all your investments. This could include stocks, bonds, funds, cash, real estate, etc. You might hear someone say "my portfolio is 70% stocks, 30% bonds" – that describes their asset allocation. Managing your portfolio means overseeing this collection and periodically balancing it according to your goals and risk tolerance.

Index: A statistical measure of the stock market or a segment of it, based on a weighted collection of stocks. Major examples: S&P 500 (500 large U.S. companies), Dow Jones Industrial Average (30 prominent U.S. companies), Nasdaq Composite (over 3,000 mostly technology stocks on the Nasdaq exchange). Indexes are used to gauge market performance ("the S&P 500 is up 1% today") and as benchmarks for investors. You can't invest directly in an index, but you can buy an index fund that replicates its holdings. An index fund is a mutual fund or ETF designed to track a specific index – giving you broad market exposure with low costs. For instance, an S&P 500 index fund will hold the stocks of the S&P 500 in the same proportions, aiming to match its performance. Index investing is a popular, passive strategy for beginners and experienced investors alike.

ETF (Exchange-Traded Fund): A type of investment fund that trades on an exchange like a stock. An ETF holds a basket of assets (e.g., stocks, bonds, commodities) and issues shares that investors can buy. For example, there are ETFs that track indexes (SPY tracks the S&P 500), sectors (XLK for tech stocks), themes, countries, etc. ETFs offer "one-click" diversification – by buying one share, you effectively invest in all the components of the fund's basket. They combine the diversification of mutual funds with the trading flexibility of stocks. Most ETFs are passively managed index funds, but some are actively managed. They have become one of the most useful tools for investors to get exposure to various market areas easily and cheaply.

Dividend: A portion of a company's profits paid to shareholders, typically on a quarterly basis. For example, a company might declare a dividend of $0.50 per share every quarter – if you own 100 shares, you'd receive $50 each quarter. Dividends are a way for companies to reward shareholders and share the wealth. Not all stocks pay dividends (many growth companies do not). Dividend yield is a key term here – it's the annual dividend divided by the share price, expressed as a percentage. If a stock is $100 and pays $4 in dividends per year, the yield is 4%. Yields let you compare income potential. Remember, dividends can be reinvested to compound returns, and historically dividends contributed a large portion of total stock returns.

Capital Gain (and Loss): The profit or loss made when you sell an investment for a different price than you bought it. If you buy a stock at $50 and later sell at $70, you have a $20 capital gain per share. If you sold at $40 instead, you'd have a $10 capital loss. Capital gains can be realized (when you sell and lock in the profit) or unrealized (paper gains on investments you still hold). Tax-wise, short-term capital gains (on assets held ≤1 year) are usually taxed at higher ordinary income rates, while long-term (held >1 year) are taxed at lower capital gains rates. The goal of investing is to accumulate capital gains over time (and ideally minimize taxes on them).

Compound Interest (Compounding): In investing, compounding is the process where your investment earnings generate their own earnings. It's often called "interest on interest," though with stocks it's more like "returns on returns." For example, if you invest $1,000 and earn 10% ($100), you'll have $1,100. If you then earn 10% again, it's not another $100, but $110 (10% of the new $1,100). That extra $10 is from compounding. Over many years, compounding can lead to exponential growth of your money. Reinvesting dividends and staying invested in the market allows compounding to work in your favor. The earlier you start investing, the more compounding periods you have. This is how small, regular investments can grow astonishingly large given enough time – as we saw, $1 compounded over a couple of centuries became millions (extreme case, but it illustrates the point!). The key takeaway: time and reinvestment are compounding's best friends.

Market Capitalization (Market Cap): The total value of all a company's shares of stock. It's calculated as share price × number of shares outstanding. Market cap is essentially what the market believes the company is worth. Companies are often categorized by size: Large-cap (typically $10 billion+), Mid-cap (~$2B–$10B), Small-cap ($300M–$2B), etc.

For example, if a company has 1 billion shares outstanding and each is $50, its market cap is $50 billion. Market cap is a more comprehensive measure of company size than stock price alone. (A $100 stock could be "smaller" than a $10 stock if the first has 10 million shares vs the second having 200 million shares, for instance.) Investors sometimes use market cap to guide diversification – e.g., including some small-caps for growth potential and large-caps for stability.

P/E Ratio (Price-to-Earnings Ratio): This is one of the most common valuation metrics. It's the stock price divided by the earnings per share (EPS). It tells you how much investors are paying for each dollar of the company's earnings. For example, a stock at $50 with an EPS of $2 has a P/E of 25. A high P/E might mean the stock is expensive relative to its earnings (possibly due to growth expectations), while a low P/E might indicate it's cheap or perhaps that investors aren't expecting growth. It's often used to compare companies or to compare a stock against its historical average P/E or the market average.

A practical use: if Company A has a P/E of 15 and Company B has a P/E of 30, and they're similar in other aspects, A is valued lower (cheaper) relative to earnings. Do note, P/E has limitations (earnings can be cyclical or manipulated, etc.), but it's a great quick snapshot. There are variants like forward P/E (uses forecasted earnings) and PEG ratio (P/E divided by earnings Growth rate) which can refine the analysis.

Volatility: This refers to how much and how quickly an asset's price moves. A stock that swings 5% up or down every other day is highly volatile; one that moves only ±1% in steady fashion is low volatility. Volatility is often seen as a measure of risk – high volatility means the value of your investment can change dramatically in short periods (which can be nerve-racking, but also can mean higher potential reward). The VIX is an index measuring the implied volatility of S&P 500 options – often called the "fear index" because volatility tends to spike when investors are fearful. As a beginner, expect some volatility in stocks; it's normal. Managing volatility is about knowing your risk tolerance and time horizon (short horizon + high volatility = not a great mix).

IPO (Initial Public Offering): This is when a private company first sells stock to the public and becomes a publicly traded company. An IPO is essentially "going public." For example, if a startup decides to list on the NASDAQ, it will IPO and investors can then buy its shares on the open market. IPOs can be exciting (new company to invest in!) but also risky – there's often a lot of hype, and early trading can be very volatile. Some IPOs skyrocket, others flop. It's generally wise for beginners to be cautious around IPOs; without a long public track record, the stock's fair value can be hard to gauge.

Blue-Chip Stock: A nickname for a large, established, financially sound company with a history of reliable performance. Blue chips are often leaders in their industry, pay dividends, and are considered safer investments. Examples include companies like Apple, Microsoft, Coca-Cola, etc. The term comes from poker, where the blue chips are typically the most valuable. If someone says "I invest mostly in blue-chip stocks," they imply a conservative approach focusing on well-known companies.

As you continue learning, you'll encounter many more concepts (like alpha, beta, order types, short selling, etc.), but don't feel pressured to know it all at once.

Welcome to Your Lifelong Investing Journey

Investing in stocks is a journey. And an incredibly profitable one...

This guide has equipped you with the basics of what stocks are, why they're a compelling wealth-building tool, how to set up and plan your investing, different strategies to consider, ways to protect yourself, and key terms to understand.

The next step is to put this knowledge into action: open an account, consider your goals, maybe start with an index fund or a couple of stocks you've researched, and begin investing regularly.

Always keep educating yourself – read quality research (Stansberry Research's free publications, for example, offer a wealth of insight), stay curious about businesses, and don't be afraid to start small and learn by doing.

Remember, successful investing is about staying optimistic while also managing risk.

Stocks have rewarded optimistic long-term investors handsomely, as history shows, but the best investors pair that optimism with sensible precautions and discipline. If you can do that – keep your head in the game during the tough times and not get carried away during the euphoric times – you'll already be ahead of most.

Good luck on your investing journey, and welcome to the stock market.

You can sign up to receive free information from Stansberry Research by clicking right here.